“… le illusioni della paranoia [sono] tentativi (sia pure devianti) di riparare, di ricostruire un mondo ridotto a caos completo”.

Oliver Sachs, L’uomo che scambiò sua moglie per un cappello

Circa sette o otto anni prima del lockdown, c’erano stati segni e cambiamenti nel comportamento e nella personalità di Ciulli, alcuni dei quali poterono essere individuati solo retrospettivamente, mentre altri colpivano nel momento stesso in cui avvenivano. Scrivere questo concetto in una frase, usando parole ed espressioni familiari, seguendo le regole della grammatica e della punteggiatura, non rende l’idea della confusione e dell’isolamento che comporta la demenza. Il caos e il panico, mentre la malattia avanza, sfidano l’espressione verbale, sia della persona con demenza che di quelli che l’amano. I preziosi contenuti interiori delle nostre vite – questi vasti, sicuri, intimi santuari della mente che abbiamo costruito dalla nascita, come pure le memorie e i costrutti invisibili che creiamo nelle relazioni – sono sistematicamente vandalizzati e dissacrati nel corso della malattia. I primi segni di questa dissociazione sono terrificanti: le chiavi del santuario intimo di una persona vengono perdute, rubate dal male, minando la fiducia nella sovranità della propria mente.

Al tempo del primo lockdown, a Ciulli era stato da poco diagnosticato, da uno dei tanti specialisti, una demenza vascolare con sindrome di Parkinson, dopo tre anni di vai e vieni tra dipartimenti neurologici e psichiatrici degli ospedali e cliniche di Bologna. Benché le sue condizioni certamente andassero peggiorando, era ancora relativamente autonomo all’inizio del 2020, e ben capace di comunicare verbalmente, scegliendo con la sua consueta agilità mentale tra le quattro lingue che parlava fluentemente. Ma molti sintomi fisici si andavano aggravando: il tremore della mano destra era più evidente e più penoso; camminava trascinando i piedi e con le spalle curve; la faccia deliziosamente mutevole ed espressiva era adesso quasi sempre impassibile. La luce dei suoi occhi era cambiata e lui sembrava spesso assente e confuso. Sempre più di frequente mi avrebbe chiesto come usare le più semplici dotazioni della casa: gli interruttori, le spine e le prese erano diventate per lui fonte di confusione- Dimenticava come avviare gli elettrodomestici di cucina, come spedire un’email, come usare il telecomando della televisione, che adesso vedeva quasi di continuo. L’apatia e il disinteresse erano completamente estranei alla sua natura, come la mancanza di coordinazione nei movimenti e il disorientamento. Ogni giorno avrebbe spostato, o nascosto o perso le sue cose (chiavi, portafoglio, sigarette elettroniche e accessori, denaro, un libro che amava, i documenti d’identità) e poi con grande imbarazzo mi avrebbe chiesto di aiutarlo a trovarle. Questa situazione andò avanti da mattina a sera, ogni giorno, giorno dopo giorno durante il primo mese del lockdown. Confinato in un piccolo appartamento, solo con me e la sua confusione, Ciulli sembrava sempre meno capace di comprendere quello che accadeva intorno a lui e cogliere la realtà della pandemia. La sua crescente incapacità di fare operazioni di base trovava riscontro nella mia incapacità di capire realmente e di ricordare che era affetto da demenza. Ripensandoci, sembravo preferire litigare con lui piuttosto che accettare la verità, che il suo male era diventato impossibile da fronteggiare.

Poche settimane dopo il lockdown, all’inizio di marzo, Ciulli parlava sempre più spesso di “tipi sospetti” nel nostro cortile. In realtà c’erano pochissime persone nel cortile da quando era cominciato il confinamento, ed erano tutti dei vicini. Certo debbo aver fatto qualche osservazione sarcastica quando lui parlava degli estranei in cortile. C’era una inconsueta xenofobia nei suoi commenti. Aveva cominciato a parlare di Noi e Loro, e ad ammonirmi di frequente di stare attenta, sgridandomi perché mi fidavo troppo. Verso metà di aprile mi chiedeva perché ero così stupida. A questi insulti rispondevo con grida e ingiurie: “Ma ti rendi conto di come stai parlando? Come un bigotto piccolo borghese. Senti quello che dici. Chi sei tu?”. Probabilmente lo gridavo, con quella voce profonda da baritono che ho quando sono arrabbiata, che lui odiava, o forse lo pensavo soltanto. Come lui, io stavo avendo difficoltà a sapere se stavo pensando e cosa realmente mi usciva dalla bocca. I quaranta metri quadrati del nostro appartamento sembravano collassare in una camera di pensiero senza spazio. Litigavamo sempre di più: la sua ansietà, le sue accuse diventavano sempre più irrazionali, sempre più insultanti, sempre più piene di spavento. Arrivò a dire che questo gruppo nel cortile era rumeno, e che era parte di una banda di mascalzoni, una sorta di complotto terroristico.

“Molto probabilmente”, affermò a voce bassa, come se qualcuno potesse sentire “coinvolge anche molti di quelli che abitano nel nostro palazzo”.

I suoi occhi avevano un’impenetrabile oscurità, lo sguardo mostrava un indecifrabile groviglio di pensieri e preoccupazioni. La faccia sembrava dissimulare un abisso di sofferenza, mentre una volta esprimeva amore e curiosità. E alla fine, potevo percepire il cupo e profondo terrore che era in lui. Nella sua paranoia, il suo senso di empatia sembrava essere stato rimpiazzato da una mancanza di amore, ostile alla vita umana come lo spazio extraterrestre. Quelle onde invisibili di pensieri e sentimenti che passano da un essere umano all’altro erano adesso bandite. La malattia stava confondendo i suoi sentieri neurologici come un assassino taglia i fili del telefono prima di entrare in casa. Istintivamente io mi ritraevo, passando sempre più tempo nel cortile a comporre di giorno le mie “Ballate dell’orrore” e di sera disegnavo nel mio angolino in camera da letto.

Verso i primi di maggio, Ciulli aveva cominciato a dire che io ero parte della banda. Mi accusava di avere dei rapporti con la gente del cortile, di scomparire con loro di giorno, derubandolo, nascondendo il suo denaro, complottando e mentendo. Quando gli chiedevo di che diavolo stesse parlando, mi guardava con sospetto, mi diceva con gli occhi: “Non mi prendere per stupido. Io ti tengo d’occhio”. Queste occhiate sarcastiche mi scuotevano: non ne capivo il senso.

Un pomeriggio della fine di aprile, mentre Ciulli rientrava dalla spesa (era una delle ultime volte che poté uscire da solo), mi disse che aveva capito tutto il complotto, tutto, quindi potevo smettere di fingere.

“Di che diamine stai parlando?” fu la mia risposta.

“Sei incredibilmente brava” – disse – “Come riesci a farlo?”.

“Fare cosa?”.

“E dai, lo sai. Adesso basta. Basta. Puoi smettere di fingere… questo teatrino… tutta questa messa in scena. Lo so che è tutto finto, lo so che è una copia… Voialtri avete copiato tutto… perfettamente… i libri, i mobili, l’intera cucina… anche la cartolina su quel cazzo di frigorifero. Anche l’interno del frigorifero… Anche il cortile qua fuori… Come ci riesci? Debbo ammetterlo: voialtri siete bravi. Davvero bravi”. Era calmo. Non stava gridando, infatti. Parlava a bassa voce. Nella mia testa c’erano grida, ma non provenivano da Ciulli.

“E tu come ci riesci?” – disse sbalordito – “Davvero, come come ci riesci: i suoi comportamenti, le sue abitudini, il suo modo di parlare, di pensare… è incredibile”.

Il fatto che passasse freddamente e soprappensiero alla terza persona mi fece l’impressione di una lama che affondasse senza sforzo in un organo interno. Probabilmente barcollai.

Sentii come se mi stesse dicendo che amava un’altra donna, e che quella che gli era sconosciuta ero proprio io. Era sbalorditivo: lo stavo perdendo per un’altra donna che ero io. Lo stavo perdendo per la follia e sentivo davvero una fitta di gelosia, per la follia che stava penetrando la sua mente più profondamente di quello che avrei potuto io. Questo mi provocava una nauseante vertigine.

Gli chiesi di sedere con me sul divano, per favore, in modo che potessimo parlare. La sua docilità, la sua fiacchezza, come se avesse vagato nei boschi per giorni e io fossi una gentile estranea che lo aveva lasciato entrare, mi colmarono di pietà. Dov’era stato? In che roveto velenoso era rimasto intrappolato? Si sedette, scuotendo la testa sconsolato. Mi sembrò innaturale provare pietà per qualcuno che amavo così intimamente.

Sedetti vicino a lui e dissi: “Per favore, spiegami di che stai parlando”.

“Io colgo pezzi di lei in te, vedo sprazzi di lei, ma tu hai scelto di andare per quest’altro sentiero… quest’altro, sai… qualunque cosa tu stia facendo con il resto di loro…”. Tacque per un momento e poi chiese: “Perché… Perché… È proprio un peccato… Avresti potuto essere un’artista come lei… Io vedo differenti Amy ogni volta che ti guardo”.

Qualcosa nella maniera in cui chinò la testa quando mi guardò mi fece improvvisamente capire. Per lui io ero come quei libretti animati che amavo da bambina – pugili che menano un pugno – e mi tornò alla mente come fossi stata sbalordita dalle descrizioni di miei amici dei “sentieri visivi” che vedevano sotto l’effetto dell’LSD, le tracce affascinanti lasciate da un oggetto in movimento.

“Non ti sbagli, Ciulli” – dissi – “Stai proprio vedendo le cose in un modo che il resto di noi rimuove”.

Pensai ai cronomatografi di Étienne-Jules Marey, che piacciono a molti pittori, e che ho trovato sempre affascinanti. Il movimento – una persona che passeggia, un uccello in volo, un cavallo che corre – viene registrato su una macchina che mostra tutti i passi, in immagini che sembrano quelle del Nudo che scende le scale di Duchamp o i ritratti di Francis Bacon. Probabilmente allora menzionai questi quadri a Ciulli, sapendo che lui amava i quadri.

Parlavamo come se ci fossimo appena incontrati, parlavamo come se non avessimo parlato da anni. Era la prima volta che mi rendevo conto che se non mi fossi arrabbiata o spazientita, potevamo effettivamente ancora parlare. Gli chiesi di dirmi di più, per cortesia, dirmi tutto, tutto quello che poteva.

A modo suo descriveva come vedeva la moltiplicazione di Amy minuto per minuto, secondo per secondo. Tutto, dovunque guardasse, era una copia. io immaginavo il suo cervello come una stampante da computer bloccata. Io, e qualunque cosa nella stanza, apparivamo come una stampata inarrestabile, sottile come carta: da nessuna parte niente di reale, da nessuna parte niente di vero o sostanziale.

“Conosco quella sensazione, Ciulli, ho provato qualcosa di simile… è terrificante. Ma posso dirti che io sono reale. Forse ci sono altre versioni di me in altre dimensioni che io non posso vedere ma tu sì, ma ti posso assicurare che anche questa Amy qui è reale”. La mia mano era sulla sua spalla, le nostre ginocchia si toccavano.

Sembrava sollevato.

Fin dall’infanzia sono stata affascinata dal modo in cui vediamo, in parte per il puro piacere sensuale della vista, per la pienezza lussureggiante di quel senso, e in parte perché se si conosce il meccanismo coinvolto nella visione, ci si trova faccia a faccia con l’artificio del mondo materiale e si sollevano le domande più profonde sulla natura dell’essere. Sentivo che il cervello di Ciulli stava disimparando il meccanismo cognitivo della visione: da qualche parte nell’infanzia il nostro cervello impara a collegare le immagini separate che vengono proiettate sulla retina in un’idea apparentemente solida e riconoscibile di una persona o di un oggetto. Stava disimparando come elaboriamo i meccanismi fondamentali della vista, o forse dimenticando o confondendo quella fase precoce dello sviluppo che lo psicologo infantile Jean Piaget ha chiamato “permanenza dell’oggetto”. Ogni volta che sono stato colpita dal ricordo subliminale di esperienze traumatiche, ho provato il panico silenzioso di vedere le mie percezioni improvvisamente alterate. Perdere improvvisamente le nostre abitudini percettive acquisite crea una sensazione di irrealtà e di dislocazione tanto sconvolgente e spaventosa quanto un brutto viaggio da acido.

“Stai percependo cose che impariamo a non percepire, Ciulli. Io so quanto può essere spaventoso. Lo capisco”.

“Sai, vedo lampi del pensiero di mia moglie in te, la sua mente… Penso che le saresti piaciuta… Mi sarebbe piaciuto che vi foste incontrate”.

Con un tonfo silenzioso, l’ascensore della percezione volò di nuovo via dalle sue pulegge, precipitando in una profondità senza fondo, e la vertigine nauseante tornò. È straziante essere percepita come un’impostora dalla persona più vicina a te. È straziante amare qualcuno così profondamente, che persino perderlo a causa della follia ti rende gelosa della follia. È straziante amare qualcuno, sia che sia sano di mente sia che sia pazzo. Tuttavia, la sua espressione d’amore per me, pur credendo di stare parlando di me a qualcun’altra, era insopportabilmente triste, proprio perché lui pensava di parlare a qualcun’altra.

Circa un minuto dopo mi disse che aveva dimenticato di cosa avevamo parlato. Rise molto dolcemente, timidamente, dolce come la pioggia. Non lo sentivo ridere da molti mesi.

Senza impazienza, glielo ripetei. Numerose volte. Era confortante per me sentire che potevo confortarlo. C’era una tenerezza reciproca e una curiosità reciproca. Parlammo dolcemente per tutta la sera.

La notte, però, non fu dolce. Da diverse settimane Ciulli metteva in scena i suoi sogni, prima nel letto, poi nell’appartamento: colpiva violentemente le cose dal comodino o scalciava selvaggiamente le gambe o dava pugni al cuscino vicino al mio viso. Poi una notte iniziò a vestirsi per andare a un colloquio di lavoro alle tre del mattino. Un’altra notte, più o meno alla stessa ora, mi svegliai con l’odore di carta bruciata. Lo trovai ai fornelli, mentre infilava un pezzo di carta arrotolato nella fiamma. Lo inseguii intorno al minuscolo tavolo della cucina finché non riuscii ad afferrare la carta in fiamme dalle sue mani e a gettarla nel lavandino prima che potesse dare fuoco alle tende.

Una mattina presto, mentre ero a letto, mi svegliai e lo vidi fissare il soffitto con occhi spalancati: aveva bagnato il letto. Mi chiese dove fosse la sua testa: “È in cima o in fondo a me?”. Non ricordo come risposi. Ho solo un vivido ricordo del mio senso di orrore per quella domanda.

Durante le ultime settimane di isolamento, iniziò a rimanere sveglio la maggior parte delle notti parlando con una stanza piena di rumeni visibili solo a lui; lo tenevano in ostaggio e dalle sue parole e dal suo tono di voce, potevo dire che questi esseri disincarnati erano senza cuore. Per ore e ore ho ascoltato le sessioni di interrogatorio unilaterali: Ciulli in piedi ai piedi del letto che urlava, imprecava, supplicava i suoi invisibili rapitori di lasciarlo andare. Era straziante sentire la sua angoscia, la sua frustrazione, la sua rabbia – che aumentava e diminuiva, aumentava e diminuiva – una marea continua e implacabile di paura e di furia nell’oscurità. Durante quella notte e molte altre, mi svegliavo e cercavo di calmarlo, ma era inutile: ero esausta, lui era impazzito. Per lo più cercavo solo di dormire un po’ per poter affrontare il giorno dopo.

Ricordo poco di quelle ultime settimane. Abbiamo mangiato? Chi ha cucinato? Avevo chiamato gli amici per dire loro cosa stava succedendo? Andavo in bagno per chiamare periodicamente la clinica psichiatrica senza che lui mi sentisse, o lo facevo davanti a lui per fargli capire che non avevo segreti per lui? So che per la maggior parte del tempo ha creduto che l’appartamento fosse solo una copia del nostro appartamento a Bologna e che lui fosse in realtà in Romania. Credeva di essere stato rapito e portato in una cella di terroristi in Romania. Voleva uscirne. Credeva che sua moglie, Amy, fosse detenuta in un’altra cella da qualche parte, forse in un altro paese. Cosa le avevano fatto? Sapeva che ero un’impostora, ma sembrava che gli piacessi più degli altri rapitori. Pensava sempre che fossi un’impostora o a volte ero la vera Amy? Era sempre in Romania o solo a volte?

A metà maggio, quando finalmente il lockdown cominciò a diminuire gradualmente, chiamai il servizio di salute mentale e chiesi un appuntamento il prima possibile. Era urgente, spiegai nel mio italiano stentato: “Mio marito è psicotico e io sono pericolosamente priva di sonno”.

Quando arrivammo alla clinica c’era una lunga fila. Cerano lunghe file ovunque durante la pandemia, tutti “praticavano il distanziamento sociale”, obbedienti e circospetti come scolari. Vedere gli italiani, così naturalmente anarchici e resistenti alle regole, obbedire ora a ogni nuovo editto – per quanto controintuitivo o contraddittorio sembrasse – faceva riflettere, era terrorizzante. Eravamo tutti terrorizzati. Tutti, ovunque, sembravano terrorizzati. Tutti, dappertutto, avevano le maschere. C’era qualcosa di orribile in questa silenziosa mandria di volti mascherati, file di occhi spaventati, vuoti o arrabbiati, senza naso né bocca. C’era qualcosa di orribile in questo tranquillo conformismo e nella rapidità con cui la paura aveva reso tutti noi acquiescenti all’esecuzione degli ordini … tranne Ciulli. Continuava a togliersi la maschera, mormorando: “Non ci sto a queste stronzate”. Ma senza discutere mi permetteva di rimettergliela, ancora e ancora. La ripetizione sembrava calmare entrambi. Mi chiedevo se pensasse che tutte queste persone mascherate fossero terroristi. Mi chiedevo se pensasse che fossimo tutti rumeni.

Alla fine furono chiamati i nostri nomi. Avevo già avuto diverse telefonate con alcuni medici della sua équipe psichiatrica; avevo già raccontato loro dei sogni notturni di Ciulli, dei rapitori invisibili provenienti dalla Romania, della sua convinzione che tutti, compreso me, fossero degli impostori e che tutto nel nostro appartamento fosse una replica. Quando fu chiamato il nostro nome, fui sollevata dal fatto che fossimo accolti dal medico preferito di Ciulli, un tirocinante molto giovane e dalla parlata dolce, che ci condusse nel suo angusto ufficio. Ciulli parlò per primo in modo libero, semplice, calmo, descrivendo la sensazione che tutto fosse una copia, il non sapere dove si trovasse, il sentirsi sospettoso di tutti e di tutto. Ricordo che sembrava profondamente sollevato di parlare con questo medico, che era una persona evidentemente premurosa e intelligente, e lo ascoltava come una persona. “Questa è la sindrome di Capgras”, disse infine il giovane medico, “di solito è associata alla demenza corporea di Lewy”. Il suo tono era gentile e fermo, il suo sguardo sensibile e diretto, senza paura. Vidi come le sue parole, la sua voce empatica, fossero di profondo conforto per Ciulli. Chiesi al medico di scrivere su un foglio di carta quei nomi impossibili da capire che aveva appena pronunciato.

Prendemmo appuntamento per tornare tra un paio di settimane, quando sarebbe stata presente l’intera équipe di medici psichiatrici e assistenti sociali di Ciulli. Sentivo che il peggio doveva ancora venire? Ero troppo esausta per prendere in considerazione questa o altre ipotesi. La prima ondata di Covid si stava ormai diffondendo in tutto il mondo e dei vaccini non c’era traccia. Non pensavo e non sentivo nulla: erano tre mesi che ci trascinavamo sul pavimento, pancia a terra. Ero intontita.

PART 1 – CHAPTER 2: NAMING

“… the delusions of paranoia [are] attempts (however misguided) at restitution, reconstructing a world reduced to complete chaos.”

– Oliver Sacks, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat

About seven or eight years before the lockdown, there were signs and changes in Ciulli’s behavior and personality—some remarkable only in retrospect, others shocking at the moment they were happening. Writing this thought in a sentence, using familiar words and idioms, following rules of grammar and punctuation, belies the mayhem and isolation that comes with dementia. The chaos and panic as the disease progresses defies verbal expression, for both the person with dementia and for the people who love them. The precious interiors of our lives—those vast, safe, inner sanctums of the mind that we have dwelt in since birth as well as the memories and invisible constructs we create in relationships—are systematically vandalized and desecrated in the course of the disease. The first signs of that desecration are terrifying: the keys to one’s inner sanctum have been lost, stolen by the disease, ravaging one’s trust in the sovereignty of one’s own mind.

At the time of the first lockdown, Ciulli had been recently diagnosed with vascular dementia with Parkinsonian syndrome by yet another specialist, after three years of being bounced back and forth between neurological and psychiatric departments in Bologna’s hospitals and clinics. Though his condition was certainly worsening, he was still relatively autonomous at the beginning of 2020, and very capable of communicating verbally, choosing with his usual mental agility among the four languages he spoke fluently. But many physical symptoms were worsening: the tremor in his right hand was more obvious and more painful; he walked with a shuffle, shoulders stooped; his delightfully malleable and expressive face was now impassive most of the time. The light in his eyes had changed, and he often seemed absent and confused. More and more frequently he would ask me how to use the most basic household amenities—light switches and electrical plugs and sockets had become confusing to him; he forgot how to turn on kitchen appliances, how to send an email, and how to operate the remote control for the television, which he was watching almost continuously now. His apathy and disengagement were completely out of character, as was his clumsiness and disorientation. Every day he would misplace or hide or lose his personal belongings—keys, wallet, e-cigarettes and paraphernalia, cash, a favorite book, ID cards—and then sheepishly ask me to help him look for them. This went on from morning to night, every day, day after day after day during the first month of the lockdown. Isolated inside a small apartment with just me and his confusion, Ciulli seemed less and less able to comprehend what was going on around him and the reality of the pandemic. I mirrored his increasing inability to do basic tasks in my inability to truly realize and remember that he had dementia. In retrospect, I seemed to prefer arguing with him rather than accepting the truth that his disease was becoming overwhelming.

A few weeks after the lockdown in early March, Ciulli was more and more often talking about “suspicious characters” in our courtyard. The fact was there were very few people in our courtyard since home confinement began, and they were all neighbors. No doubt I made some kind of sarcastic rejoinder when he commented on the foreigners in the courtyard. There was an uncharacteristic xenophobia in his comments. He had begun talking in terms of Us and Them, and frequently admonishing me to be careful, chiding me for being overly trusting. By mid-April he was asking me how I could be so stupid. In response to these insults, I resorted to yelling and name-calling: “Do you hear how you sound? Like a petit bourgeois bigot. Listen to yourself! Who are you?!” I probably bellowed it, in the deep baritone voice I have when I’m angry, which he hated, or then again maybe I just thought it: Like him, I was having difficulty knowing what I was thinking and what was actually coming out of my mouth. The forty square meters of our apartment seemed to be collapsing into a spaceless thought chamber. We were squabbling more and more; his anxiety and accusations were growing steadily more irrational, more insulting, more panicked. He made a point of mentioning that this group in our courtyard was Romanian, and they were part of a nefarious cadre, some kind of terrorist plot.

“Quite likely,” he stated quietly, as if someone might hear, “it involves many of the people in our own apartment building.”

His eyes contained an impenetrable darkness; his brows showed an indecipherable tangle of thought and worry. His face seemed to mask a chasm of anguish where once love and curiosity had been. At last, though, I could sense the depth-dark terror within him. In his paranoia, his sense of empathy seemed to have been replaced by a lovelessness as unsustainable to human life as outer space. Those invisible waves of thoughts and feelings that emanate from one human being to another were now dammed up. The disease was jumbling Ciulli’s neuropathways like an assassin scrambles the telephone wires before entering the house. I instinctively recoiled, spending more and more time in the courtyard composing my “Horror Ballads” during the day and drawing in my little corner of the bedroom at night.

By the beginning of May, Ciulli was saying I was part of the cadre. He accused me of having affairs with the people in the courtyard, disappearing with them during the day, stealing from him, hiding his money, scheming and lying. When I asked him what the hell he was talking about, he looked at me askance, saying with his eyes, Don’t take me for a fool, I’m on to you. That sneering glance shook me; I could make no sense of it.

One afternoon in late April, when Ciulli returned from grocery shopping (it was one of the last times he would ever go out alone), he told me that he was on to the whole plot, the whole thing, so I could stop pretending.

“What the hell are you talking about?” was my response.

“You’re all incredibly good at this,” he said, “How do you do it?”

“Do what?”

“C’mon, you know. Just stop. Stop. You can stop pretending … the whole act … the whole set-up here. I know everything is fake, I know it’s a copy … You guys have copied everything … perfectly … the books, the furniture, the whole kitchen … even the postcard on the fucking refrigerator. Even the inside of the refrigerator. … Even the outside courtyard … How do you do it? I’ll say this: You guys are good. Real good.” He was calm. He wasn’t yelling, in fact, he spoke quietly; inside my head there was screaming but it wasn’t coming from Ciulli.

“And how do you do it?”he said in wonderment. “Really, how do you do it—her mannerisms, her habits, her way of talking, thinking … it’s incredible.”

That off-handed switch to the third-person mid-thought felt like a blade smoothly slicing into an internal organ. I probably flinched.

It felt as if he were telling me he was in love with another woman, who it turned out, unbeknownst to him, happened to be me. It was dizzying: I was losing him to another woman who was me; I was losing him to madness and actually felt a twinge of jealousy for the madness for penetrating his mind more deeply than I could. It produced a nauseating vertigo.

I asked him to please sit down with me on the couch so that we could talk. His compliance, his weariness, as if he had been wandering in the woods for days and I was a kindly stranger who had let him come in, filled me with pity. Where had he been? What poisonous bramble had he been caught in? He sat down, shaking his head forlornly. It felt unnatural to pity someone I loved so intimately.

I sat down next to him and said, “Please explain to me what you’re talking about.”

“I catch pieces of her in you, I see flashes of her, but you chose to go down this other … path … this other, you know … whatever it is you’re doing with the rest of them …,” he paused for a moment and then asked, “Why? … Why? … It’s such a pity. … You could have been an artist like her … I see different Amys every time I look at you.”

Something about the way he cocked his head when he looked at me made me suddenly understand: For him, I was like those tiny page-flip animation books I loved as a kid—boxers throwing a punch—and I flashed back on how entranced I was by friends’ descriptions of the “visual trails” they saw on LSD, the mesmerizing traces left by a moving object.

“You’re not wrong, Ciulli,” I said, “You’re just seeing things in a way that the rest of us filter out.”

I thought about Etienne-Jules Marey’s chronophotographs, which like many painters, I have always found fascinating. Movement—a person walking, a bird in flight, a horse running—is recorded on a machine showing all the steps, in images that look like Duchamps’ Nude Descending the Stairway or Francis Bacon’s portraits. I probably mentioned those paintings to Ciulli then, knowing how much he loved paintings.

We talked as if we were just meeting, we talked as we hadn’t talked in years. It was the first time I realized that if I didn’t get angry or impatient, we could actually still talk. I asked him to please tell me more, tell me everything, anything he could.

In his own way he described how he saw different Amy’s proliferating minute by minute, second by second; everything, everywhere he looked, was a copy. I imagined his brain was like a computer printer gone haywire: I, and everything in the room, appearing like unstoppable printouts, flimsy as paper—nowhere anything real, nowhere anything true or substantial.

“I know that feeling, Ciulli, I’ve experienced something like that … it’s terrifying. But I can tell you, I’m real. Maybe there are other versions of me in other dimensions that I can’t see but you can, but I can promise you, that this Amy here is real too.” My hand was on his shoulder, our knees were touching.

He seemed relieved.

Since childhood I’ve been fascinated by the way we see—in part because of the sheer sensual pleasure in the sense of sight, the luscious fullness of that sense, and in part because if one knows about the mechanism involved in seeing, it brings one face to face with the artifice of the material world and raises the deepest questions about the nature of being. I could feel that Ciulli’s brain was unlearning the cognitive mechanism of seeing— somewhere in infancy our brains learn to connect the separate images that are projected onto the retina into a seemingly solid, recognizable idea of a person or object. He was unlearning how we process the fundamental mechanics of sight, or maybe forgetting or jumbling that early developmental stage that the child psychologist Jean Piaget named “object permanence.” When I have been triggered by the subliminal recall of traumatic experiences, I have felt the silent panic of having my perceptions suddenly altered. Suddenly losing our acquired habits of perceptions creates a feeling of unrealness and dislocation as jarring and frightening as a bad acid trip.

“You’re perceiving things we learn to tune out, Ciulli. I know how scary that can be. I get it.”

“You know, I see flashes of my wife’s thinking in you, her mind … I think she would have liked you … I wish you two could have met.”

With a silent thud, the elevator of perception went flying off its pulleys again, plummeting into a bottomless depth, and the nauseating vertigo returned: It is harrowing to be perceived as an imposter by the person closest to you. It is harrowing to love someone so deeply that even losing them to madness makes you jealous of the madness. It is harrowing to love someone whether they are sane or insane. Yet his expression of love for me while believing he was talking to someone else about me was unbearably poignant precisely because he believed he was talking to someone else.

About a minute later he told me he had forgotten what we had been talking about. He laughed very softly, shyly, gentle as rain. I hadn’t heard him laugh in many months.

Without impatience, I repeated it. Numerous times. It was comforting for me to feel I could comfort him. There was a mutual tenderness, and reciprocal curiosity about each other; we talked gently all evening.

Nighttime though was not gentle: For several weeks Ciulli had been acting out his dreams, first in the bed, then in the apartment—violently knocking things off the nightstand or kicking his legs wildly or punching the pillow next to my face; then one night he started getting dressed to go to a job interview at three a.m. Another night, at about the same hour, I awoke to the smell of burning paper. I found him at the stove, sticking a rolled-up piece of paper into the flame. I chased him around the tiny kitchen table until I could grab the flaming paper out of his hands and throw it into the sink before he could light the curtains on fire.

Lying in bed early one morning, I awoke to him staring wide-eyed at the ceiling; he had wet the bed. He asked me where his head was: “Is it at the top or the bottom of me?” I don’t remember how I replied, just a vivid memory of my own sense of horror at the question.

During the last weeks of the lockdown, he began staying up most of the nights talking to a roomful of Romanians visible only to him; they were holding him hostage and by his words and his tone of voice, I could tell these disembodied beings were heartless. For hours and hours, I listened to the one-sided interrogation sessions: Ciulli standing at the foot of the bed yelling, cursing, pleading with his invisible captors to let him go. It was excruciating to hear his anguish, his frustration, his rage—mounting and subsiding, mounting and subsiding—a continuous, relentless tide of fear and fury in the darkness. Throughout that night and many others, I would rouse myself and try to calm him, but it was useless—I was exhausted, he was insane—mostly I just tried to get some sleep in order to be able to get through the next day.

I remember little of those last weeks: Did we eat? Who cooked? Had I called friends to tell them what was going on? Did I go into the bathroom to periodically call the mental health clinic without him hearing, or did I do it in front of him so that he knew I had no secrets from him? I know most of the time he believed the apartment was just a copy of our apartment in Bologna and he was actually in Romania: He believed he had been kidnapped and had been taken to a terrorist cell in Romania. He wanted out. He believed his wife, Amy, was being held in another cell somewhere—maybe in some other country. What had they done with her? He knew I was an imposter, but he seemed to like me better than the other captors. Did he always think I was an imposter, or was I sometimes the real Amy? Was he always in Romania, or just sometimes?

By the middle of May, when at last the lockdown began to gradually lift, I called the mental health service and asked for an appointment as soon as possible. It was urgent, I explained in my broken Italian: “My husband is psychotic, and I am dangerously sleep-deprived.”

There was a long line when we got to the clinic; there were long lines everywhere during the pandemic, everyone “practicing safe social distancing,” as obedient and circumspect as school children. Seeing Italians, so naturally anarchic and resistant to rules, now obeying every new edict—no matter how counter-intuitive or contradictory it seemed to be—was sobering, frightening. All of us were frightened. Everyone, everywhere, seemed frightened. Everyone, everywhere, had masks on; there was something horrifying about this quiet herd of masked faces—queues of scared or blank or angry eyes with no noses or mouths. There was something horrifying about this quiet conformity and how quickly fear had made us all acquiesce to following orders—except for Ciulli. He kept taking his mask off, muttering, “I’m not going along with this shit.” But without argument he would let me put it back on him, again and again. The repetition seemed to calm both of us. I wondered if he thought all of these people in masks were terrorists. I wondered if he thought we were all Romanians.

Finally our names were called. I had already had several phone calls with several of the doctors on his psychiatric team; I had already told them about Ciulli’s all-night waking dreams, the invisible captors from Romania, his conviction that everyone, including me, was an imposter and everything in our apartment was a replica. When our name was called, I was relieved we were greeted by Ciulli’s favorite doctor, a very young, soft-spoken intern, who led us into his cramped office. Ciulli talked first—freely, easily, calmly—he described feeling that everything is a copy, not knowing where he was, feeling suspicious of everyone and everything. I remember he seemed deeply relieved to be talking with this doctor, who was an obviously caring and intelligent person, who listened to him like a person. “This is Capgras syndrome,” the young doctor finally said, “It’s usually associated with Lewy Body Dementia.” His tone was gentle and steady, his gaze sensitive and direct and without fear. I saw how his words, his empathetic voice, were deeply comforting to Ciulli. I asked the doctor to write those impossible-to-understand names he had just said on a piece of paper.

We made an appointment to come back in a couple of weeks, when Ciulli’s entire team of psychiatric doctors and social workers would be present. Did I sense the worst was yet to come? I was too exhausted to entertain that notion, or any other for that matter. The first wave of Covid was now rippling all around the globe and vaccines were not anywhere on the horizon. I wasn’t thinking or feeling anything: We had been dragging ourselves across the floor on our bellies for three months, I was numb.

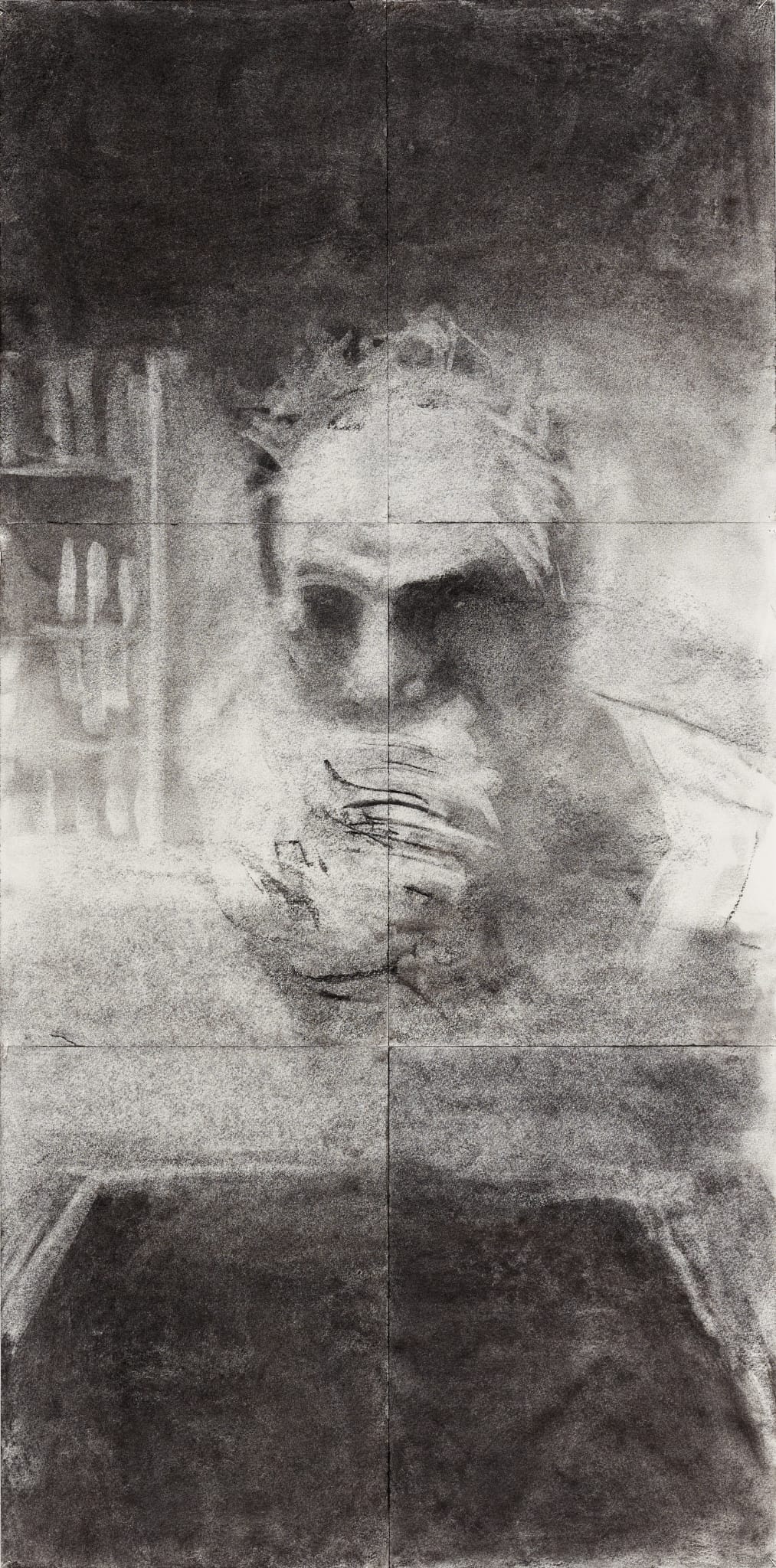

In copertina: AM Hoch, Who Remains? (2024)